“Your job isn’t to build more software faster: it’s to maximize the outcome and impact you get from what you choose to build”. — Jeff Patton.

Surviving the agile landscape

I have worked on dozens of projects using agile methods with great results. Agile is empowering business and product teams alike, during MVE (most valuable experience) development, to evolve from concept to new product introduction in a limited timeframe, and also on incrementally renovating existing products.

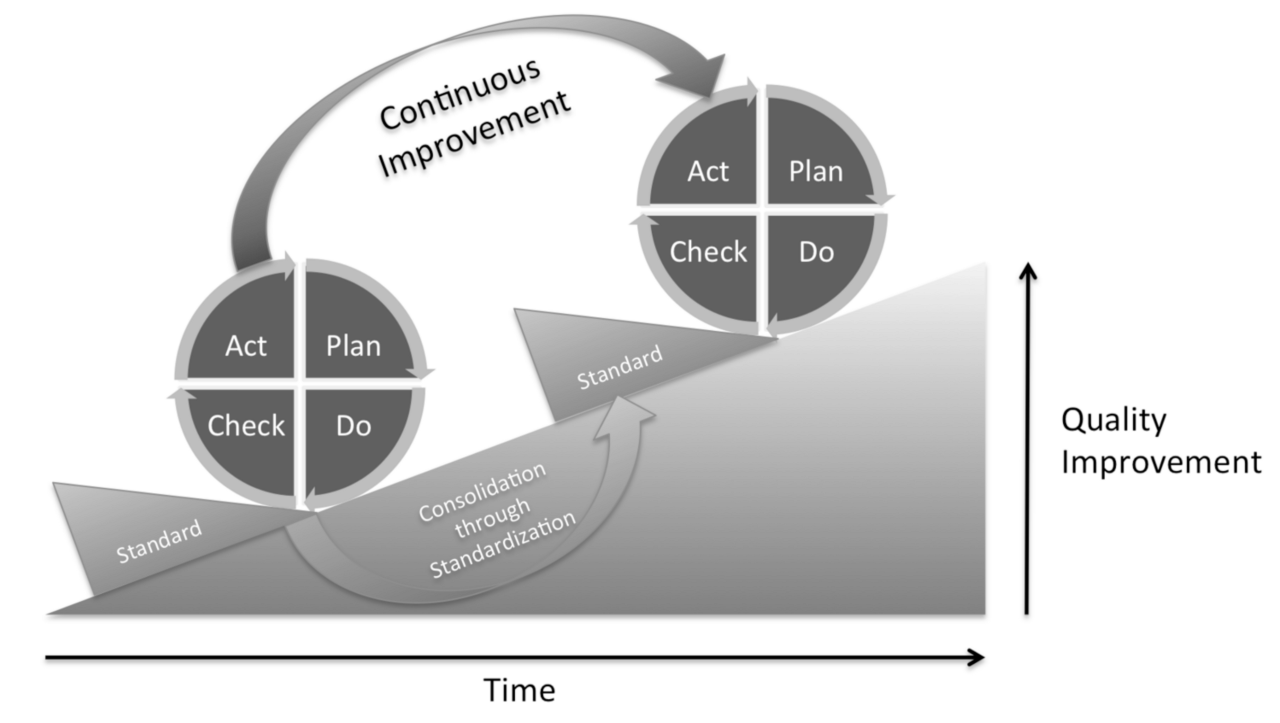

As designers, we naturally gravitate towards the customer-centricity of agile with its overarching objective to deliver valuable software, early and often. However, it is within these agile processes of continuous improvement (and continuous delivery), where designers struggle with maintaining a constant pace.

The most challenging aspect of agile is the conflict between its ideology and accomplishing it on the ground. Agile creates a sense of urgency, which is useful in focusing and motivating the team. However, I have seen first hand that this immediacy can be a source of consternation for designers because it often means they do not have enough time to do what they need to do. This limitation curtails the designer’s agency to problem solve effectively and leads to them bypassing essential steps in their due diligence and processes.

Your love is like bad medicine

In the foreground, designers adapt to survive and succeed within agile workflows. Over time, new coping mechanisms emerge that encourage bad habits that impede design practice. We learn how to be more flexible as priorities continuously shift. We spend less time analysing and reflecting as we make increasingly efficient decisions, without supporting evidence. We endure the prioritisation of “go-to-market” over quality control. We start to let things go that previously would have been dealbreakers for us.

All the while, our ideology, rigour and standards retreat into the background. We justify our new selves by commending our flexibility, praising our inner strength to “let things go” and propping our compliance with the new world order of product development. We wonder, are we not picking battles because we are waiting for the one worth fighting for, or is it because our beliefs and confidence have been undermined by groupthink and the promise of an effective process to deliver valuable software.

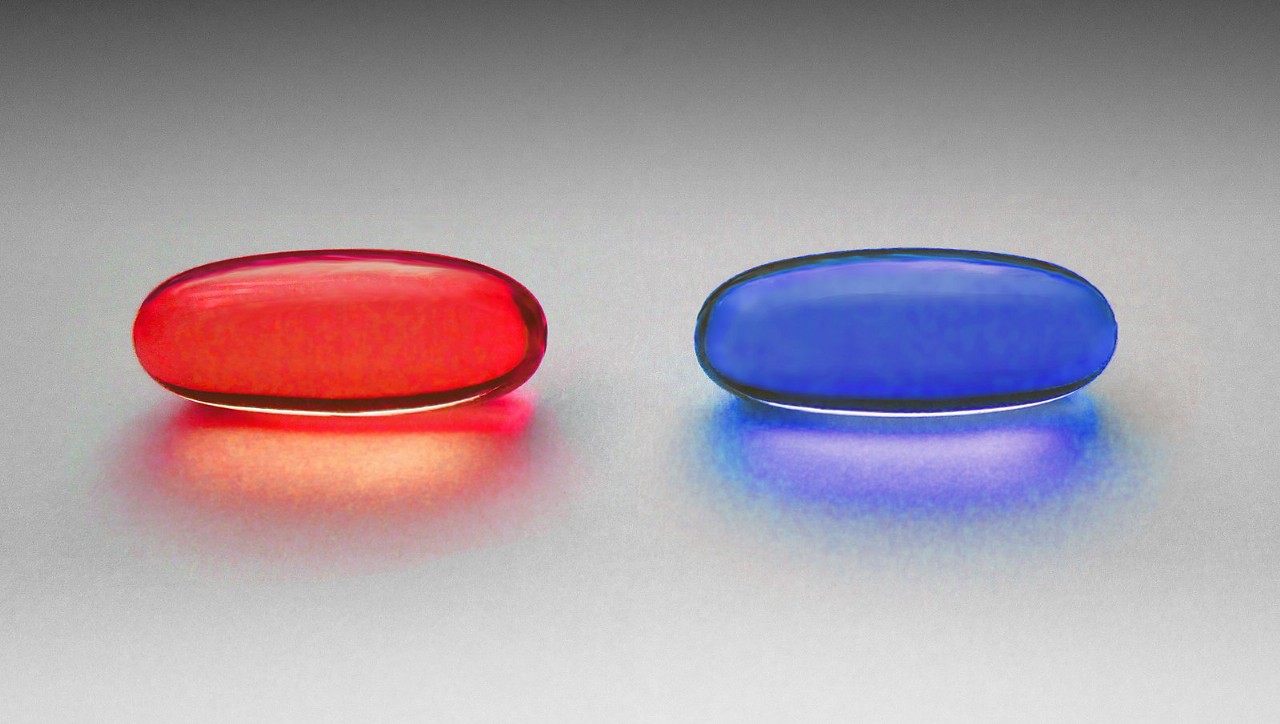

The red or the blue pill

When a designer becomes aware of the chasm between their professional potential and the constraints that the surrounding operational structure imposes on them, there are two paths. Option one is to keep going and continue to try and cope with cultural or systemic failures where the organisation undervalues design and diminishes the designer’s role as a change-maker and problem solver. In this environment, it is easy for the designer to become the silent endorser of a poor process. They will inevitably get overloaded, stretched thin — hopefully not to the point of burnout.

The other option is one of personal and professional affirmation, which leads to moving forward, and away, from the constraints of unhealthy practice. They search for a position that provides equilibrium, reassurance and positivity — a safe space where their voice can shape a difference.

In an ideal world

So, how can we create a sustainable agile environment and process that maintains a constant space for designers? Indeed, part of a designer’s skill is to be the tap pouring out solutions to various kinds of problems that emerge on an ongoing basis. These are table stakes to work on agile, so I’m not going to worry about that. Also, the designer role of wearing the user t-shirt and being the representative for the “outside-in” perspective seems to work well within agile — so I’m not going to focus on that either.

Instead, I want to zoom in on what I see happening in the field, where designers are not thriving in the agile environment. I want to start to unpack where and why designers find the agile methodology challenging to work within.

To perfect, or not to perfect, that is the question

I wouldn’t say I like shipping unresolved or mediocre design solutions — no matter how well coded or technically excellent they are. The design process for me is all about opening and closing the box based around a fixed set of goals and constraints.

There will always be deadlines, and they help incentivise the designer to commit and pull everything together. Still, sometimes there is not enough time on agile projects — say within a 1-week sprint — to be able to resolve the design. And this never sits well with a designer.

This lack of resolution is because the time allocated to complete the design is too tight for the scope of the project. We can deconstruct the archetypal design process into a series of explorations, critiques and revisions. This robust and effective process is disrupted within agile when we:

- curtail the number of necessary iterations

- avoid reviews from significant stakeholders

- deviate from design best practice and methodology, or

- skip essential steps in the design process

These disruptions will harm the design resolution, which diminishes the quality of the overall delivery from the particular sprint. There is an inherent conflict between the time constraints of, for example, a 1-week sprint and providing the designer with enough time to resolve the design.

Redesign the agile structure with epic results

The agile process has to accommodate the designers’ workflow without disrupting the entire scrum team(s) flow. The first step relates to the values of the work culture and requires that the organisation takes designers and their needs more seriously.

By managing and improving the structure of agile projects, we can ensure design gets the equal footing it deserves. Here are some examples of changes to the agile workflow that I have seen benefit the design teams and, ultimately, the quality of the product.

- Start running dedicated design sprints that focus entirely on the look, feel, structure and flow of the product. Resolved design is the deliverable from the sprint — it’s like our equivalent of usable code or working software. The focus of the sprint is solely on design. Still, it does not have to exclude non-designers — product owners, devs and business folk are welcome to attend and participate in brainstorming and reviews — but ultimately, the sprint is for the benefit of the design team.

- Start to stagger sprints so that the dedicated design sprints, mentioned in the last point, occur in advance of, and feed into build sprints. In this model, the designers get a head start on opening the box, defining the problem, brainstorming many solutions and synthesising solutions that are resolved before the dev team start building it.

- Provide designers with experimenting time to conduct design exploratory work such as:

- inventorying and analysing the design from other parts of the product family

- ideation and sketching out possibilities relating to UI grids, layouts, components and elements.

- exploring interaction design systems, patterns and style guides

- Provide designers with extra dedicated time early and often in the process to validate design decisions with real users through user interviews, usability testing (user testing) or workshop facilitation. These can be conducted by the design team or in collaboration with researchers or research teams.

Case study

While working on a recent project, the objective was to renovate a planning tool that had 3 main problem spaces. We allocated time for the designers to work together on dedicated design sprints.

- Design Sprint 1: we dedicated the first of 4 x 2-week sprints to experimenting time for the designers to discover and prepare for the design sprints ahead of time.

- Design Sprints 2–4: Each of the subsequent 3 x 2-week sprints focused on 1 of the 3 main problem spaces of the planning tool.

The Dev team also had 4 dedicated 2-week build sprints to code solutions, but their sprint 1 started the same week as design sprint 2. This staggering of sprints following the head start given to designers meant that the designers had enough time to do their due diligence, make mistakes, and to breathe.

In conclusion

Principle 7 of The Agile Manifesto is:

“Agile processes promote sustainable development. The sponsors, developers, and users should be able to maintain a constant pace indefinitely.”

My interpretation of sustainable development relates tothe overarching product development (not just coding) — so it’s remit should include designers — and their needs, plus the mechanisms and supports that will ensure they can maintain a constant pace indefinitely, and most importantly — mindfully!

Happy designing!

Here are some other articles by Séamus Byrne. If you would like to Séamus to help you with your Design Operations, you can ping him at: info AT seamusbyrne DOT net